|

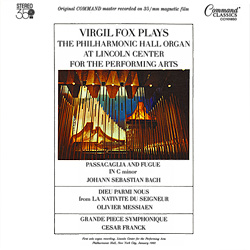

Program Notes

First solo organ recording

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Philharmonic Hall, New York City, January 1963

Organs are notoriously difficult to record. The grand "organ sound" that is so enveloping and thrilling in live performance is actually a minute blend of the basic pitches of the pipes with a rainbow of overtones determined by the pipes' characteristic shape and material, not to mention the positions in space of the various sections of the organ and the acoustical properties of the hall. The finer the instrument, the more colorful its disposition, the more stupendous are the problems to be solved in capturing its grandeurs on a record.

When Enoch Light decided to tackle the brand new Aeolian-Skinner organ at Philharmonic Hall in Lincoln Center, he knew that he had an adversary which would respond adequately only to the finest modern recording techniques, applied with infinite patience. The instrument was an unknown quantity. It had been installed over the summer of 1962 but had not made its debut until December of that year. Built in five manual divisions plus pedal organ, with 98 ranks of pipes—totaling 5.498 separate sounds, ranging in size from 32 feet to three quarters of an inch, the new organ had been designed to encompass all styles from the dear piquancy of the baroque to the sonorous fullness of Franck and Widor.

One of the world's foremost organ virtuosos was also to be reckoned with. Virgil Fox could be counted on to make full use of all of the new instruments possibilities. The pieces which Mr. Fox had selected for the recording were spread over the three major eras of organ literature —baroque, romantic, and modern — and were intended to demonstrate the versatility of the world's newest concert organ in America's newest concert hall. With his flair for color and effect. Mr. Fox would not hesitate to pull out all the stops. from the softest celeste to the most thunderous bombarde.

Mr. Light, with engineers Robert Fine and Robert Eberenz, made a thorough acoustical tour of Philharmonic Hall and spent an entire day studying the effects of the organ sound in different sections and levels. Two days in January, 1963, were allotted for the recording session. It was decided that the moveable clouds should be pulled all the way up to the ceiling for maximum bass response and that the multiple tones of the rich instrument could best be caught in three-channel stereo by a battery of microphones hung from the ceiling: six of them in pairs, evenly spaced across the stage against the organ screen; and three, also evenly spaced, above the outer edge of the stage.

The solution proved to be inspired, and the quality of sound caught by Command's 35 mm magnetic film is unparalleled in recording history. "Never before," says Mr. Fox, "have I been able to register pieces for a recording session exactly as I would for a live concert." Mikes have a way of hearing an entirely different blend of partials than human ears, and ordinary recording tape condenses the sound impulses to its own narrowness. The breadth of 35 mm magnetic film. however, allows the tones to expand to full resonance, with the result that on this recording the organ resounds for the first time in completely life-sized dimensions. Stereo fans will be interested in the spatial arrangement of the six organs. From right to left: Bombarde Organ, part of the Pedal Organ, Positiv Organ, Choir Organ and Swell Organ (in the center), Great Organ and second part of the Pedal Organ.

In its efforts to create the best organ recording possible, Command brought in the largest amount of equipment that Philharmonic Hall had ever housed for a session. Cables were strung behind the grillwork, which screens the organ pipes, by technicians crawling on catwalks among the works. For each session, the clouds had to be lowered to the floor while the mikes were being set and then raised back up to the ceilings. As the sessions extended over two days, the whole setup had to be torn down for an evening concert and reinstalled the next morning at 6 A.M. Moreover, benches and other moveables had to be insulated against sympathetic vibrations that were evoked by the massive organ sonorities.

"Any organ has its own feeling," explain engineers Bob Fine and Bob Eberenz, and by a superb blend of study and intuition the genuine "feeling" of Aeolian-Skinner's Philharmonic Hall organ has yielded to recorded sound. The clarity of the 16- and 32-foot pedal stops and the amazing tonal quality of the extremes of loud and soft achieved by Command are astonishing.

The virtuosity of Command's recording is second only to the virtuosity of the performer. Virgil Fox builds up Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor gradually, starting with a simple, baroque-type reed in the Choir and expanding into the diapason stops, those fundamental organ tones that, until the present recording, have always defied successful reproduction. In the later variations, the clear-speaking chiff (spurt of air at the beginning of the tone) of the baroque stops can be distinctly heard, echoing back and forth from Positiv to Great, from Choir to Bombarde.

For Messiaen's "Dieu Parmi Nous" from La Nativité du Seigneur, Mr. Fox following the composer's directions, opens up the full manual and pedal organs. Such a full sound is reproduced by ordinary tape as a gnarled mass of undifferentiated roars, but for the first time 35 mm. film has broken the barriers. The listener can actually distinguish the multitude of organ voices from each other in the pile of sound.

The greatest test of Command's know-how came with Franck's Grande Pièce Symphonique. In recording sessions, it is usually necessary to play the softer parts of the music somewhat louder than in recital, a conventional tape cannot catch nuances at low volume. Thirty-five mm. film, however, is subject to no such restrictions, and the wide dynamic range and variegated timbres in this piece can be heard with all the splendor, warmth, and clarity of the 19th-century French style that Mr. Fox would bring to an actual concert.

Since his debut at nineteen, Virgil Fox has played on each of the many organs located in the finest concert halls throughout America, and it was not only fitting that be should give the first solo recital on the new Philharmonic Hall but also that be should be the one to make the first recording of this outstanding instrument. Regularly organist at the Riverside Church in New York City, Mr. Fox has amassed an immense knowledge of organs, based on world-wide concertizing on both old and new instruments from Westminster Abbey to Bach's own Thomaskirche in Leipzig. The pieces performed on this record were especially chosen from Mr. Fox's supremely successful recital at Philharmonic Hall, which preceded the sessions for this album.

|

|

|

|

Original Cover - Select image to enlarge

|

Original COMMAND master recorded on 35 mm magnetic film

The original master for this COMMAND CLASSIC was recorded on 35 millimeter magnetic film rather than on 1/4-inch or 1/2-inch tape. 35 mm magnetic film recording offers many advantages over more conventional tape recordings. These advantages become most important and exciting in the recording of very large orchestras.

- Film has no flutter because of the closed loop sprocketed guide path which holds it firmly against the recording head.

- 35 mm film is more than four times as wide as the 1/4-inch tape, thus the film is able to curry the equivalent of three 1/4 - inch tape tracks with more than enough space between each track to guarantee absolute separation of channels.

- The thickness of the film—5 mils — (three times thicker than tape) greatly reduces the possibility of contamination by print-through.

- Excellent frequency response is assured by the fast speed at which the film travels — 18 inches per second, or ninety feet per minute, and the low impedance head system.

- The wider track allows for a very wide, previously unheard of range of dynamics without distortion.

- The great tensile strength of film and the sprocket drive effectively eliminates any pitch changes due to "tape stretch."

- Signal to noise ratio is far superior.

TECHNICAL DATA

This record is an example of the finest quality sound fidelity that can be achieved with a multiple microphone pick-up. From the origin of the sound in a largo acoustically perfect auditorium to the editing and the final pressing of the record, only the finest equipment is used. Some of tho microphones used, representing the best of all manufacturers available, are: the Tolefunken U-47, the RCA-44 BX, Telefunkon KM 56, Altec 639 B, RCA-77D and special Church microphones.

The reason for the multiplicity of microphone types is to insure that the optimum instrumental sound will be reproduced by use of the microphone whose characteristics are most complimentary to that particular instrument.

Recording is from 35 millimeter magnetic film through a Westrex RA 1551 reproducer. The sound signal is fed through a specially modified Westrex cutting head which is installed on an Automatic Scully lathe fitted with variable electronic depth control and variable pitch mechanisms.

From the preparation of the acetate master to the final stamper used to make this copy, all phases of the manufacturing process are carefully supervised and maximum quality control is exorcised to the highest degree known at the present state of the industry.

RIAA standards are fully complied with in these new COMMAND CLASSICS and for the best results we recommend that standard RIAA reproduction Characteristic Curve for each channel should be used.

Great care should be exercised in the selection of the stereo cartridge — properly adjusted for optimum tracking force and a minimum of tracking error — and, when played through a two-channel reproducing system of quality workmanship this COMMAND CLASSIC will delight the most discriminating audiophile.

|